The choice of law applicable to the contract

In an International Contract it is essential to include the clause defining the law governing the contract.

Subject to exceptions, this choice is freely implementable between the parties.

In the EU, the Regulation (EC) No 593/2008.

The choice of applicable law must be expressly stated pursuant to Art. 3.

In the absence of choice, the general criterion is based on the concept of the party to provide the characteristic performance (which will never be the performance of paying a sum of money).

For example, in a contract of sale, it is the right where the seller is based.

The above rules do not apply to consumer contracts, contracts relating to rights in rem in immovable property, contracts of carriage, for which other connecting factors apply

When choosing the applicable law, certain cautions should always be borne in mind, such as

coordinating the choice of applicable law with the choice of competent court.

The choice of competent court

In an International Contract it is essential to include a clause defining the competent court or arbitration in case of disputes.

It will have to be taken into account whether the judgment issued in one country is then enforceable in another country.

It would make no sense to provide for a choice of court clause to decide the dispute arising from the contract if the judgment rendered by that court could not be recognised and enforced in the foreign country where the party against whom it is addressed is domiciled.

Arbitration

With arbitration, the parties renounce submitting disputes arising from the contract to state courts and refer them to the judgement of third parties (whom they choose, either directly or mediated, according to the regulations of the Arbitration Chamber of their choice), whose decision (award) has the capacity to obtain the same effect as a judgement rendered by state courts.

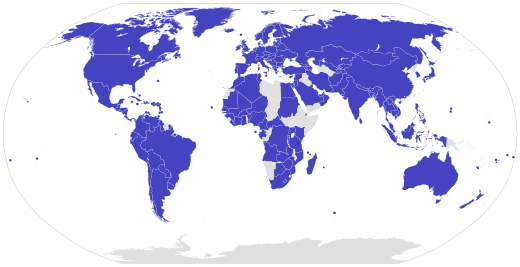

The most important Convention on international arbitration is the 1958 New York Convention, which has been ratified by a very large number of states (www.uncitral.un.org).

This Convention entails the obligation of the acceding states to recognise and enforce foreign arbitral awards.

The most important limitation of the arbitration process is its high cost. Cameroon signed the convention

Moment of transfer of ownership and risks of property loss /1

Civil Law Countries are divided, in this matter, into three large groups, the prototypes of which can be respectively indicated:

- in the French Code Napoleon of 1804

- in the German BGB of 1900

- in the Austrian ABGB of 1811

Countries following the rules of the Austrian ABGB require three requirements for the transfer of ownership:

- consent

- the cause

- delivery of the thing

The countries that refer to the German BGB reduce the requirements for the transfer of ownership to two, which are:

- consent

- delivery

Time of transfer of ownership and risks of loss of property /2

Countries that refer to the Code Napoleon identify the requirements:

- in the consensus

- in the case

The latter is the principle of transferable consent also expressed in Article 1376 of the Italian Civil Code: "in contracts having as their object the transfer of ownership of a specific thing, the creation or transfer of a right in rem or the transfer of another right, the ownership or right is transmitted or acquired by the consent of the parties legitimately given".

Where the consensualist principle the seller performs the obligation to deliver the thing to the buyer by handing over to the buyer the good which is already the buyer's property.

One acquires ownership and, with it, the right to dispose of things even before having received delivery and, therefore, before having paid the price.

The passing of the risk of perishing

The passing of the risk of the perishing of the thing sold is governed by the principle res perit domino (the thing perishes in the hands of the owner) in both the transactional consent system and the BGB system.

The Common Lawhas further emphasised in this matter the need to respect the will of private parties by laying down the rule that it is for the contracting parties to determine at what moment ownership passes, whether at the time of the conclusion of the contract or at the time of delivery or payment of the price.

The problem arises in practice if the parties have not stipulated when the moment of transfer occurs.

This problem is solved by following the criterion that property passes, according to the presumed will of the parties, at the time of the conclusion of the contract, in accordance with the consensual principle.

However, unlike in Civil Law, the passing of risk is in the hands of the person who directly or indirectly has the availability of the goods, hence the birth of Incoterms.

Force majeure - force majeure and undue hardship clause

The obligation to pay damages is not absolute, it is not triggered every time a party fails to perform properly.

The limit is that of the supervening impossibility of performance.

A party is not liable for non-performance if it is proved that it was due to an impediment resulting from circumstances beyond its control and which it could not reasonably have foreseen at the time of the conclusion of the contract.

The Force Majeure Clause consists ofin an event that is by its nature as unpredictable as it is inevitable, completely outside the will of the debtor, new and different from what the parties could reasonably foresee at the time of the conclusion of the contract.

The Clause hardship(supervening excessive onerousness) has as its basis an event that creates an imbalance between the contractual performances such as the parties had intended at the time of the conclusion of the contract and on which the parties had relied (the event does not make performance impossible, but renders it extraordinarily burdensome).

Given the low legal relevance of contingent onerousness (hardship) in the systems of common law it is a good rule, when operating in that area, not to simply leave it to the national law applicable to the contract to substitute the will of the parties, otherwise one runs the risk of finding oneself at the mercy of rules very different from those of civil law and a complex and unpredictable jurisprudence for a jurist of civil law.

However, because of the importance of the profile, international sales contracts often contain clauses to deal with the hypothesis of supervening excessive onerousness:

- the first solution is a clause requiring the parties to attempt to agree on a revision of the contract, if they do not reach an agreement, the supplementary rules of law come into play.

- The second solution is a clause requiring the parties to seek agreement to revise the contract, and in the absence of agreement to entrust a third party with the task of finding and advising the parties on a possible solution modifying the contract. The parties may accept it or not; if they do not accept it, the law comes into play.

- The third possibility, by far the most usedis the clause requiring the parties to seek an agreement and if they fail to reach one, to instruct a third party to find a solution binding on the parties (arbitration).

This is the most effective clause as it gives the parties the opportunity to seek agreement and, if there is no agreement, brings in a third party who decides and saves the contract.

The Execution of the International Contract

Fulfilment (performance) is the exact performance of the performance due.

An international contract, like a domestic contract, must be executed in accordance with the principles of good faith and fair dealing.

Discharge and liquidated damages

The Resolution is certainly the most radical of the measures resulting from the non-performance of the contract i.e. non-performance.

It is usually accompanied by damages. Only non-performance characterised by a certain gravity may give rise to termination.

In Italian law The latter principle is condensed in Article 1455 of the Civil Code.

Similar rules can be found in all legal systems: for example, the Vienna Convention - C.I.S.G. 1980 - on the international sale of movable corporal goods, in Articles 25 and 46 speaks of fundamental breach.

The assessment of the gravity of the non-performance, in the silence of the parties, is always a matter for the court.

This is the reason why in drafting a contract it appears important to include clauses that result in the prior identification by the parties of those obligations the breach of which may lead, if desired, to the termination of the contract (express termination clause Art. 1456 of the Civil Code).

As for damages, the problems that frequently arise concern not only their proof but also their quantification.

What is meant by compensable damage in the light of the law regulating the contract? The following questions may be asked in response:

- whether only damages directly resulting from the non-performance or also indirect damages are compensable;

- whether and to what extent an equitable assessment of the damage caused is possible;

- whether or not regard is to be had to the aggravation of the harm dependent on subjective reasons of the non-performing party;

- whether only foreseeable damage is compensable.

It follows that precisely in order to avoid the problems mentioned above, it will be advisable, if and insofar as possible, to include clauses in contracts that provide for suitable means to avoid them or in any event to minimise them or finally to pre-empt them as is the case with the inclusion of a penalty clause.

Penalty clauses ('liquidated damages')

Their purpose is to make a prior determination of the amount of damages and a lump-sum settlement of the damages without the need to go to court, i.e. without the need for the person who suffered the damage to prove its amount before a judge.

The language of the contract

The linguistic problem is a concern for those working on a practical level, because if a contract is drafted in Italian and translated by a translator who is not too well versed in the legal field, there is a risk that the latter, not understanding the concepts and differences, will translate in such a way as to change the meaning of the contractual text.The importance of language use has stimulated international contracting, where English plays a major role, to develop the following remedies:

- definitions clausecontracts contain a part, usually at the beginning of the contract, in which the parties clarify the meaning of certain expressions that could lead to doubts of interpretation;

- original text clausethe parties identify the version of the contract in a particular language as the only original.

Le consequences are as follows: the original version is the only authentic version, the others are unauthorised translations, so that if the parties dispute the meaning of the contract, the court hearing the dispute must rely on the original version to resolve the problem.

In general, there has been a tendency in international trade law to develop a language for "insiders".

Beyond the meanings attributed to the various words in the various legal systems, the language of international trade and international trade law in particular increasingly uses terms whose meaning is known to all operators, whatever their nationality.